Five things we learned from the Bank of Papua New Guinea’s latest bulletin

The Bank of Papua New Guinea recently released its December 2015 Quarterly Economic Bulletin, which provides a snapshot of the nation’s economic and financial performance over 2015. Business Advantage PNG provides five key insights.

1. PNG’s problems are financial, not economic

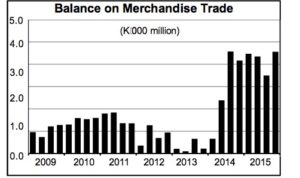

PNG’s merchandise trade account. Source: Bank of PNG

The widely reported foreign exchange issues do not reflect PNG’s overall economic position. The country has no problem with either trade or economic performance.

The country’s trade account increased in surplus from K12.9 billion in 2014 to K16.9 billion in 2015. This equates with a massive 33 per cent of GDP. Merchandise exports increased by 6.9 per cent. Imports declined, partly as a result of the restrictions on foreign exchange.

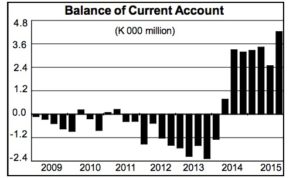

PNG’s Current Account. Source: Bank of PNG

Overall economic activity was also strongly positive. The current account, which measures income from goods, services and other transfers in and out of the country, more than doubled in 2015 to K13.39 billion. This is equal to 26 per cent of GDP. It means that PNG is a net lender to the rest of the world, not a borrower.

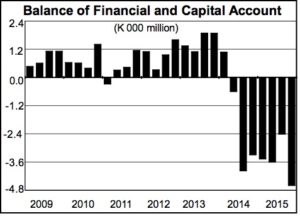

So what is causing the foreign exchange crisis? The answer can be seen in the financial account, which measures financial flows in and out of PNG. This sharply deteriorated: from a K6.8 billion deficit in 2014 to K13.95 billion deficit in 2015 (equivalent to 26 per cent of GDP).

PNG’s financial and capital account. Source: Bank of PNG

The cause? The financial requirements of the large resources companies. The Bulletin says: ‘(The financial account deficit) reflected a build up in foreign currency account balances of mining, oil and LNG companies under the various Project Development Agreements.’

In a recent interview with Business Advantage PNG, Governor of the Bank of Papua New Guinea, Loi Bakani, explained that large resource projects come with large debts.

‘Basically, when [resources companies] export, it stays in the foreign currency accounts,’ he says. ‘What they bring in is what they need for their local commitments. While it is abroad it stays in US dollar accounts, or whatever, then they pay to the lender of the loans.

Bank of PNG Governor Loi M Bakani

‘When you have development projects of this nature you have the private sector debt much higher. The private sector projects, in the loan procedures, have first call on the loan.’

2. The PNG economy is subject to high levels of volatility

The PNG economy was hit hard by the El Nino drought and the effects were clear to see in the statistics. In the September quarter of 2015, sales in the minerals sector declined by 20.7 per cent, by 18.6 per cent in agriculture, forestry and fisheries, by 10.7 per cent in retail and by 6.3 per cent in manufacturing.

There were also varying regional effects. Sales fell by a massive 63 per cent in the June quarter in the Southern region because of the closure of the Ok Tedi mine.

Direct taxes are projected to increase by 8.8 per cent, while indirect taxes are projected to increase by 45.7 per cent.

Non-petroleum export volumes fluctuated greatly in 2015. The volume of gold exports fell by 10 per cent and copper volume fell by 48.2 per cent, mainly because of the closure of the Ok Tedi mine. Crude oil export volumes were down by 19.7 per cent. The volume of coffee, cocoa, copra, rubber and logs exports all fell in 2015. The weighted average price of exports also declined by 10.2 percent in 2015.

3. The government is relying more on indirect taxes

There is a growing reliance on indirect tax revenues. Total government revenue fell by 4.7 per cent in 2015 to K8.79 billion (about 17 per cent of GDP). Direct tax revenue fell by 12.5 per cent. By contrast, indirect taxes (which include the GST), rose by 3.7 per cent.

The bulletin states that the trend towards levying more indirect tax revenue will continue this year. In 2016, while direct taxes are projected to increase by 8.8 per cent, indirect taxes are projected to increase by a mammoth 45.7 per cent.

4. Government debt has worsened

The report says total public debt at the end of 2015 was K18.2 billion—a rise of 24 per cent on the year before. This equates with 35.7 per cent of GDP, which is above the ceiling set by the 2006 Fiscal Responsibility Act of 30 per cent (35 per cent in 2013–14).

The increase in debt has not substantially increased exposure to the international capital markets, however. The report says 79.4 per cent of the deficit of K2.532 billion was financed from domestic sources. The remainder, from external sources, mainly comprised concessional loans that have comparatively easy conditions.

5. The economy’s prospects are good

The forecasts for economic growth are strong, especially when compared with expectations for the global economy. The bulletin says PNG’s economy is expected to grow by 4.3 per cent this year.

The report says there is likely to be a ‘return to trend in the gas sector after absorbing the impact of the LNG production in 2014 and 2015.’ It anticipates a rebound in the mining and non-mining sectors and improvements in global economic growth. Preparations for the 2018 Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation summit are also expected to provide a boost.

The Bank says inflation was 6.4 per cent in 2015, compared with 6.6 per cent in 2014. It is maintaining a neutral monetary policy stance. Monetary policy has been unusually stable. The Bank’s official interest rate (Kina Facility Rate) has remained unchanged at 6.25 per cent since July, 2013.