Will Papua New Guinea eliminate its fiscal deficit by 2027? Devpolicy’s Kingtau Mambon and Alyssa Leng analyse debt, budget deficit and ‘glimmers of hope’ to answer this pressing question.

Credit: Devpolicy

PNG’s Vice-Minister for International Trade and Investment, the Kessy Sawang, once described the PNG government as being ‘addicted to debt’. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also described PNG as being at high risk of overall debt distress.

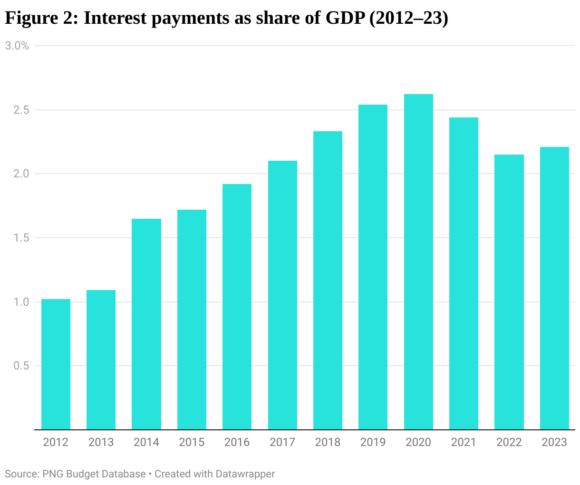

‘While 20 toea for every kina the government collected in revenue went to interest payments in 2020, only 14 toea per kina of revenue will go towards interest payments in 2023.’

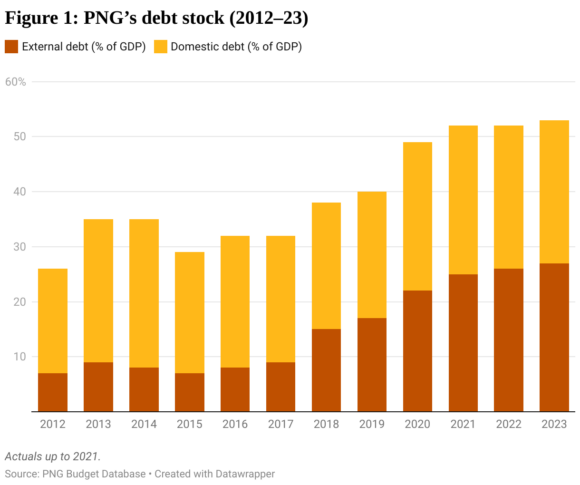

PNG’s public debt grew from around 27 per cent of GDP in 2012 to above 50 per cent in 2023 on the back of persistent budget deficits. However, recent years have shown some improvements.

Devpolicy

Firstly, the ratio of debt to GDP has stabilised since 2021 (Figure 1). Rapid nominal GDP growth due to high global commodity prices partly explains this. But the budget deficit has also been reduced. After a massive pandemic-induced deficit of K7.3 billion (9 per cent of GDP) in 2020, the deficit is now projected to fall to 4 per cent as a share of GDP in 2023.

Secondly, interest payments have also fallen relative to GDP (Figure 2), and debt servicing payments have declined as a share of government revenue. While 20 toea for every kina the government collected in revenue went to interest payments in 2020, only 14 toea per kina of revenue will go towards interest payments in 2023. PNG lowered its debt service costs by participating in the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in 2020 and 2021. In addition, interest rates have declined as PNG has accessed cheaper external financing, mostly from multilateral and bilateral institutions, and domestic interest rates have also fallen.

‘While 2023 budget documents show that PNG has a K4,238 million stock of arrears, the bill may be even larger than this.’

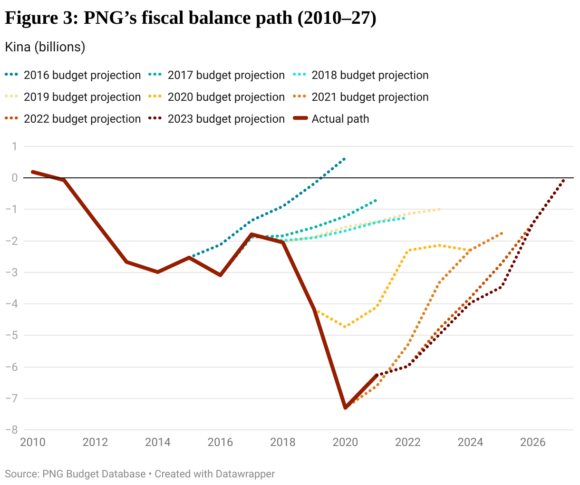

The 2022 and 2023 budget documents show a commendable plan to eliminate the deficit by 2027. However, this is easier said than done. As Figure 3 shows, PNG has struggled in recent years with fiscal consolidation despite repeated efforts to achieve it.

There are several reasons why the country will continue to struggle with the difficult task of deficit reduction.

Devpolicy

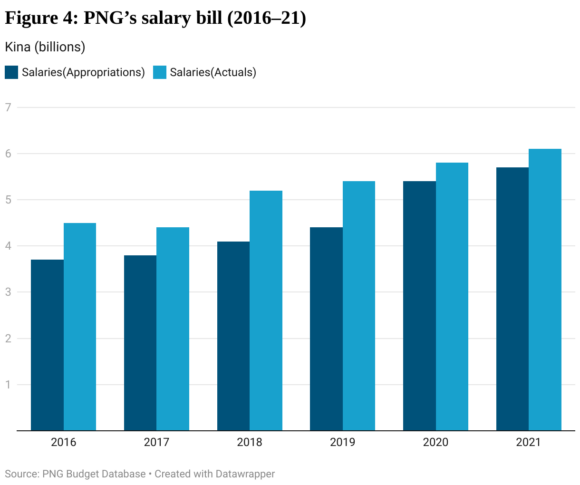

For starters, control over the [public service] salary bill remains weak. Salaries accounted for almost half the total revenue (less grants) between 2016 and 2021 and continue to exceed appropriations yearly (Figure 4).

PNG’s salary bill has previously been described as ‘impossible to predict’. Part of the difficulty here is that provinces effectively determine the number of teachers and the national government then has to pay for them. Unsurprisingly, over K500 million of personal emoluments liabilities were identified during the 2023 budget process.

Devpolicy

Arrears also remain a significant issue. The 2019 due diligence exercise found ‘significant government arrears that were outstanding and unrecognised’, with the bill increasing even after the exercise was concluded. And, while 2023 budget documents show that PNG has a K4,238 million stock of arrears, the bill may be even larger than this. While the 2021 Final Budget Outcome states K74 million of rental arrears remain outstanding, Nambawan Super has suggested that the state owes them alone K140 million in rental arrears.

Thirdly, there is little economic incentive for PNG to exercise fiscal restraint. As the kina is no longer convertible (with foreign exchange instead being rationed), the risk of a balance of payments crisis – which in the past incentivised the government to limit the deficit – is now very low. The temptation is instead to merely postpone the reduction of fiscal deficits, as has occurred in the last decade and is starkly shown in Figure 3. PNG’s plans to enter a program with the IMF will also reinforce the need for budget repair.

Fourthly, external debt has exceeded domestic debt this year for the first time since 2006. Reliance on foreign borrowing has reduced interest costs, but increased risks. If some shock forces PNG to depreciate the kina, there will be a sudden increase in interest payments.

Fifthly, expenditure pressures remain high while revenue remains sluggish. Recent announcements from the Marape government include launching the Kumul Satellite-One Project and doubling the District Services Improvement Program per member of parliament. The risk remains that projects like these will fail to improve living standards for Papua New Guineans while adding to the country’s debt burden. The ‘total failure’ as described by Prime Minister Marape of ambitious projects like Solwara 1, which cost the state K408 million, is a particularly cautionary tale.

In conclusion, despite the glimmers of fiscal consolidation PNG has seen in recent years, it will remain extremely challenging for PNG to eliminate its deficit by 2027. Further progress with fiscal consolidation will depend heavily on political commitment, revenue growth, expenditure restraint and a return to kina convertibility.

Kingtau Mambon is currently undertaking a Master of International and Development Economics at the ANU Crawford School of Public Policy, for which he was awarded a scholarship through the ANU-UPNG Partnership. Alyssa Leng is a research officer at the Development Policy Centre, working on the Papua New Guinea economy.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University. This is the second of two articles examining fiscal consolidation in PNG, using data from the PNG Budget Database. Disclosure: This research was undertaken with the support of the ANU-UPNG Partnership, an initiative of the PNG-Australia Partnership, funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views are those of the authors only.

Speak Your Mind