Is Papua New Guinea’s economy set for its next boom? The Australian National University’s Stephen Howes and Alyssa Leng examine the current economic situation and suggest where we can to look for signs of a turnaround.

Port Moresby. Credit: Ronan Paul via Devpolicy

Since 2014, when construction for the PNG LNG project ended and the oil price fell, Papua New Guinea’s economy has been in a bust. Non-resource GDP growth has been slower than population growth, and employment has declined. But PNG is a commodity exporter, and commodity prices (and especially oil prices) have recently gone through the roof as a result of the Russia-Ukraine war.

So is the bust over and PNG back in a boom?

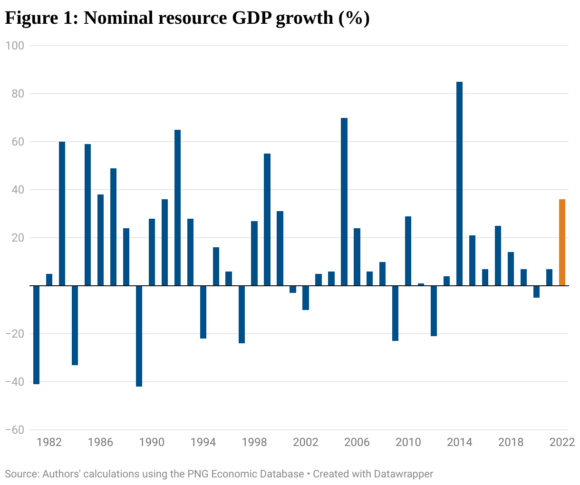

What matters when looking at the resource sector is not real but nominal growth, since both higher output and higher prices potentially lead to more spillovers to the rest of the economy.

The latest figures available from PNG’s MYEFO suggest nominal resource GDP will expand by 35.6 per cent in 2022. This is much higher than in recent years, but it is much lower than nominal growth in the resource sector at the start of previous booms. As Figure 1 shows, nominal resource GDP grew by 70 per cent in 2005 at the start of the resource boom of the 2000s, and 65 per cent in 1992 in the mini-boom of the early 1990s.

The projected expansion in 2022 is around half that size. However, the resource sector now accounts for 30 per cent of GDP and is much bigger than in earlier years—it is now almost twice the size it was in 2005. So a smaller resource sector expansion could deliver a larger boost to the rest of the economy.

Resource sector growth doesn’t always lead to more spillovers. The period from 2014 is a classic example of this: the benefits of a larger resource sector mainly went offshore—largely to the PNG LNG project, but gold projects also paid low taxes.

‘It is too early to say whether this is leading to faster economy-wide growth. The signals are confusing.’

Government coffers

A good proxy for spillovers is government revenue from the resources sector. Even accounting for inflation, resource revenues have gone up significantly in 2022. Total resource taxes and dividends are set to more than triple in real terms relative to 2021 (per the 2022 MYEFO).

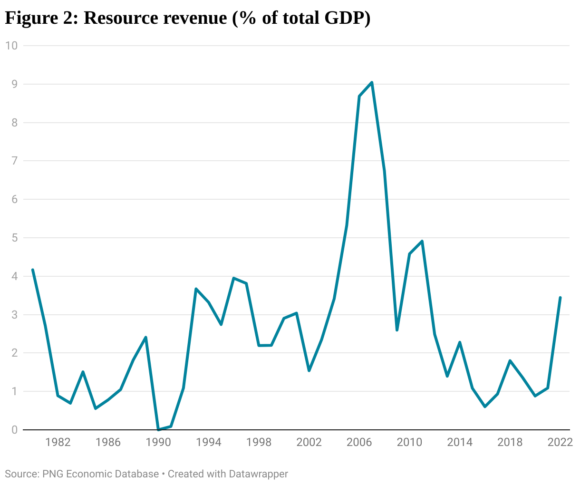

Resource revenue as a percentage of GDP is also set to reach its highest level this year since 2011 (Figure 2), and 2023 budget documents suggest that the momentum will continue.

That said, the 3 per cent of GDP that resource revenue now accounts for is nothing like the 8–9 per cent seen at the peak of the resource boom. It is instead closer to the levels achieved in the 1990s, when the boom years were short-lived and the economy was also crisis prone.

The 2022 MYEFO projects 4.4 per cent real non-resource GDP growth in 2022. But at least part of this is attributable to a bounce back from COVID-19, and it is unclear whether it will be achieved. Provisional data from the Bank of PNG shows non-mining formal sector employment has grown for two consecutive quarters and returned to a level similar to the second half of 2019. But employment levels are still lower than seen in years priors to that.

The tax take

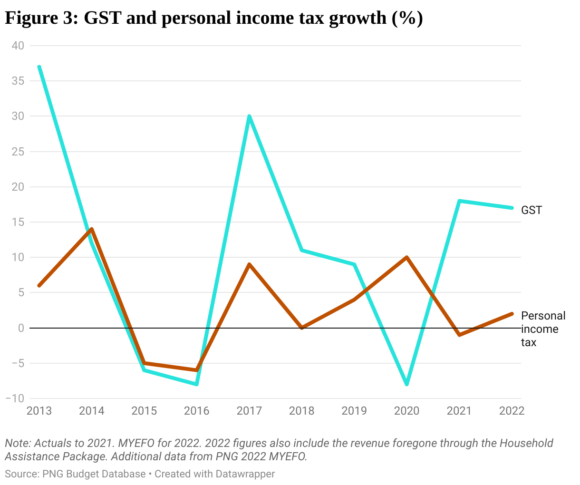

Broad-based tax collections can be a good proxy for broader economic activity.

Here, the signals are confusing, with strong growth in goods and service tax (GST) collections, but weak growth in personal income tax.

In nominal terms, personal income tax growth is estimated at only 2 per cent in 2022, following negative growth in 2021, but GST collections are growing at almost 20 per cent for the second year in a row (no adjustments for inflation). The government has made it harder for taxpayers to claim GST rebates and, as of 2020, GST can no longer be offset against personal income tax and company tax. Both may be driving rapid GST growth.

Rapid resource sector growth has boosted government revenue, but it is too early to say whether this is leading to faster economy-wide growth. The signals are confusing.

Going forward, there are two scenarios. If high resource revenues continue, we will see the boom spreading. But if oil prices fall, government revenue will fall again, and the bust will have been interrupted but not broken.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

Alyssa Leng is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre, working on the Papua New Guinea economy. Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy, at The Australian National University.

Speak Your Mind