Papua New Guinea is getting its house in order as it anticipates a period of stronger economic growth, driven in part by significant new investment in mineral production and infrastructure. In the first of a two-part series, Andrew Wilkins discusses its economy with business leaders and assesses where it is most likely to head.

The Port Moresby suburb of Konedobu, with Harbour City in the foreground. Credit: Milen Stiliyanov

A year ago, the PNG economy was seen as being in a downturn, especially when compared with the double-digit GDP growth of earlier in the decade, made possible by the massive US$19 billion ExxonMobil-led PNG LNG project.

While that project had placed PNG in the world’s top 10 gas-producing economies, the consensus among business leaders then was that PNG was set for a period of more modest growth, as it waited for the gas revenue to flow and new, transformative resources projects to eventuate.

Although there was confidence in the longer term, in the short-term profits decreased, excess jobs were shed, efficiencies were sought and sales projections were revised down.

Lower-than-anticipated global commodity prices (most notably for gas) meant the national government has been waiting longer than expected for the financial benefits from the PNG LNG project, leaving it with some tough decisions to make about spending priorities.

‘On the surface, many of the features of a low growth economy still exist.’

Meanwhile, a shortage of foreign exchange has been affecting business, both large and small.

Emerging picture

Nambawan Plaza under construction in Port Moresby. Credit: BAI

So, what has changed in the ensuing year, and what are the prospects that the Pacific’s largest economy will start to take off again in 2018?

On the surface, many of the features of a low growth economy still exist. GDP growth in 2017 fell short of the Asian Development Bank’s modest 3 per cent GDP growth prediction (it came in—according to Treasury figures—at just 2.2 per cent).

Government finances remain constrained by low revenues. The National Budget predicts GDP growth of a modest 2.4 per cent for 2018 and the O’Neill–Abel Government has entered its five-year term in July 2017 with a sober and realistic outlook.

As stated in the National Budget Strategy Paper, the government is now committed to ensuring that it ‘lives within its means, yet still pursues higher economic growth rates in a sustainable and equitable way’.

‘GST and customs revenue is set to increase.’

Indeed, the first act of the new government was to announce a supplementary budget and a 100-day plan aimed at cutting expenditure and improving tax collections and compliance.

Compliance

GST and customs revenue is set to increase, while only a fixed number of priority capital projects will be supported. The remainder will be postponed.

Compliant businesses have been particularly encouraged to see a threefold increase in the audit capacity of the Internal Revenue Commission in the 2018 National Budget.

‘Moves are also under way to open up the country’s capital markets to international investors.’

A US$500 million loan facility negotiated with Credit Suisse helped cushion government finances in the second half of 2017.

While it takes steps to bring debt back under the mandated 30 per cent of GDP ceiling, the government is looking to finance its debt in a different way by shifting from domestic to external financing.

This means that a US bond issuance program is back on the agenda for 2018, in addition to concessionary loans.

Moves are also under way to open up the country’s capital markets to international investors.

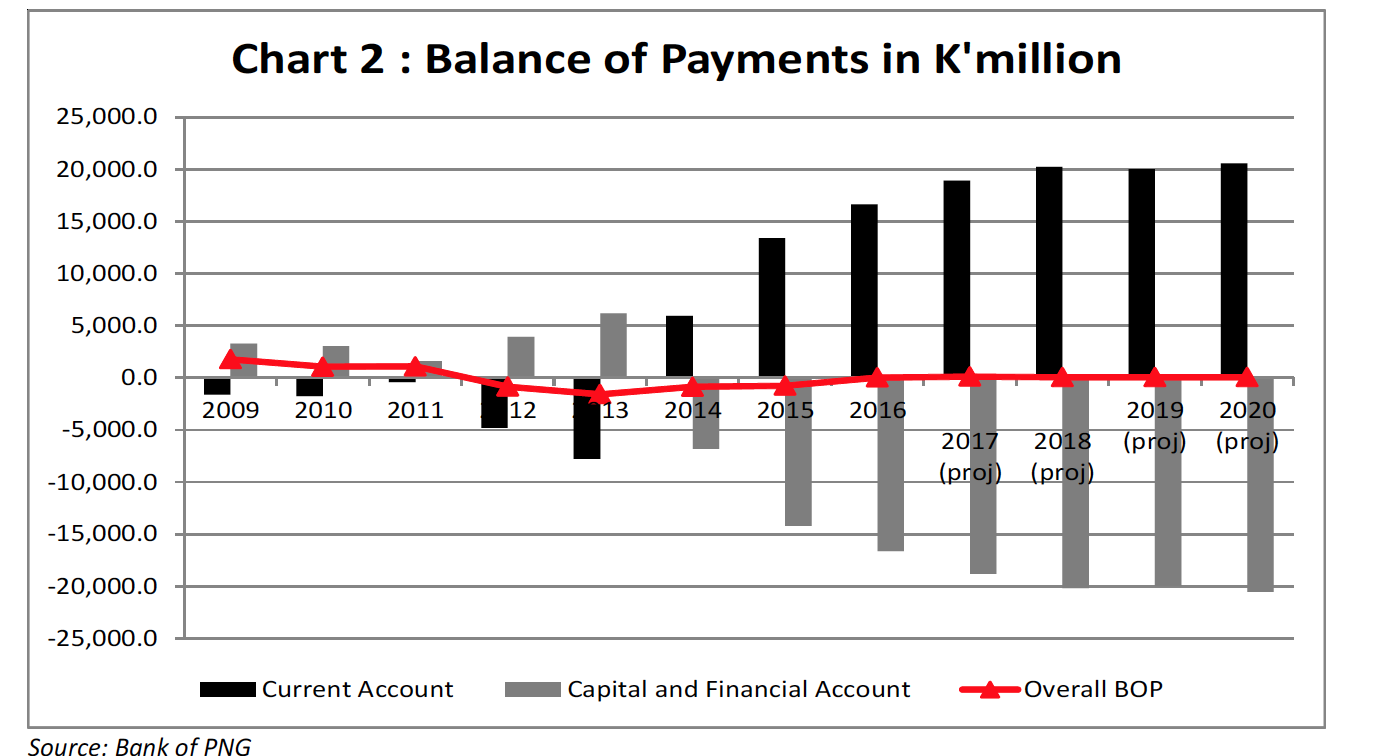

Balance of payments projections (red line). Credit: Bank of PNG

Sovereign Wealth Fund

In the longer term, it is still the government’s intention to introduce on ‘onshore managed and offshore invested’ Sovereign Wealth Fund, which would at once offer greater protection from foreign exchange shortages and help fund future infrastructure investment.

The government’s measures have been broadly endorsed internationally, with the International Monetary Fund noting that ‘the measures envisaged in the 100-Day Plan will cut the 2017 fiscal deficit significantly, to a little over 3 per cent’.

The shortage of foreign exchange continues to mean there are delays in paying for imports, repatriating profits and moving capital offshore.

In November 2017, foreign exchange reserves were less than half than what they were in 2011-12: US$1.7 billion, or the equivalent of five months’ import cover. No one is proposing a quick fix to PNG’s foreign exchange situation.

‘For certain customers it’s getting better, and for others it’s been far more difficult,’ notes Robin Fleming, Chief Executive Officer of PNG’s largest bank, Bank South Pacific.

‘The Central Bank did come in with US$100 million during October [2017], which was able to clean out part of our backlog, but there still remains quite a high level of orders outstanding.

‘The medium-to-longer term remains positive, but at the moment it’s going to be more of the same.’

Nevertheless, PNG has entered 2018 with a clearer sense of when, and where, growth will start to pick up again. Some ‘green shoots’ are already appearing.

This article first appeared in the Business Advantage Papua New Guinea 2018 business and investment guide, which is published this month. The second and final part of this article can be read here.

Speak Your Mind